The Color of Family Ties Race Class Gender and Extended Family Involvement Citation

*The American Yawp is an evolving, collaborative text. Delight click hither to improve this chapter.*

- I. Introduction

- II. Spanish America

- III. Spain's Rivals Emerge

- Four. English language Colonization

- V. Jamestown

- VI. New England

- VII. Conclusion

- VIII. Chief Sources

- IX. Reference Materials

I. Introduction

The Columbian Exchange transformed both sides of the Atlantic, just with dramatically disparate outcomes. New diseases wiped out entire civilizations in the Americas, while newly imported nutrient-rich foodstuffs enabled a European population boom. Spain benefited nearly immediately equally the wealth of the Aztec and Incan Empires strengthened the Spanish monarchy. Espana used its new riches to gain an advantage over other European nations, just this reward was soon contested.

Portugal, France, the netherlands, and England all raced to the New World, eager to match the gains of the Spanish. Native peoples greeted the new visitors with responses ranging from welcoming cooperation to ambitious violence, but the ravages of affliction and the possibility of new trading relationships enabled Europeans to create settlements all along the western rim of the Atlantic globe. New empires would emerge from these tenuous ancestry, and by the end of the seventeenth century, Kingdom of spain would lose its privileged position to its rivals. An age of colonization had begun and, with it, a great collision of cultures commenced.

II. Spanish America

Spain extended its reach in the Americas after reaping the benefits of its colonies in Mexico, the Caribbean, and South America. Expeditions slowly began combing the continent and bringing Europeans into the modern-24-hour interval The states in the hopes of establishing religious and economic dominance in a new territory.

Juan Ponce de León arrived in the area named La Florida in 1513. He found between 150,000 and 300,000 Native Americans. Merely and so ii and a half centuries of contact with European and African peoples—whether through war, slave raids, or, most dramatically, strange disease—decimated Florida's Indigenous population. European explorers, meanwhile, had hoped to find great wealth in Florida, but reality never aligned with their imaginations.

1513 Atlantic map from cartographer Martin Waldseemuller. Wikimedia.

In the first half of the sixteenth century, Castilian colonizers fought frequently with Florida's Native peoples as well every bit with other Europeans. In the 1560s Spain expelled French Protestants, called Huguenots, from the area near modern-day Jacksonville in northeast Florida. In 1586 English privateer Sir Francis Drake burned the wooden settlement of St. Augustine. At the dawn of the seventeenth century, Kingdom of spain'southward accomplish in Florida extended from the oral cavity of the St. Johns River s to the environs of St. Augustine—an area of roughly 1,000 foursquare miles. The Spaniards attempted to indistinguishable methods for establishing command used previously in United mexican states, the Caribbean, and the Andes. The Crown granted missionaries the correct to live amid Timucua and Guale villagers in the tardily 1500s and early on 1600s and encouraged settlement through the encomienda organization (grants of Native labor).1

In the 1630s, the mission organisation extended into the Apalachee district in the Florida panhandle. The Apalachee, one of the most powerful tribes in Florida at the time of contact, claimed the territory from the modernistic Florida-Georgia edge to the Gulf of United mexican states. Apalachee farmers grew an abundance of corn and other crops. Native American traders carried surplus products east along the Camino Real (the purple road) that connected the western ballast of the mission system with St. Augustine. Castilian settlers drove cattle eastward across the St. Johns River and established ranches every bit far west as Apalachee. Still, Spain held Florida tenuously.

Farther west, in 1598, Juan de Oñate led iv hundred settlers, soldiers, and missionaries from Mexico into New Mexico. The Spanish Southwest had vicious beginnings. When Oñate sacked the Pueblo city of Acoma, the "sky city," the Spaniards slaughtered nearly half of its roughly 1,500 inhabitants, including women and children. Oñate ordered one human foot cutting off every surviving male over age fifteen, and he enslaved the remaining women and children.2

Santa Iron, the outset permanent European settlement in the Southwest, was established in 1610. Few Spaniards relocated to the Southwest because of the distance from Mexico City and the dry and hostile environment. Thus, the Spanish never achieved a commanding presence in the region. By 1680, only nigh three thousand colonists called Spanish New United mexican states home.three There, they traded with and exploited the local Puebloan peoples. The region's Puebloan population had plummeted from every bit many as sixty thousand in 1600 to about seventeen thousand in 1680.4

Spain shifted strategies subsequently the military expeditions wove their way through the southern and western half of North America. Missions became the engine of colonization in North America. Missionaries, most of whom were members of the Franciscan religious order, provided Spain with an advance guard in North America. Catholicism had always justified Spanish conquest, and colonization ever carried religious imperatives. Past the early seventeenth century, Spanish friars had established dozens of missions forth the Rio Grande and in California.

Three. Kingdom of spain's Rivals Emerge

The earliest program of New Amsterdam (now Manhattan),1660. Wikimedia.

While Espana plundered the New World, unrest plagued Europe. The Reformation threw England and France, the ii European powers capable of contesting Spain, into turmoil. Long and expensive conflicts drained time, resources, and lives. Millions died from religious violence in France lone. As the violence diminished in Europe, however, religious and political rivalries continued in the New Earth.

The Spanish exploitation of New Spain's riches inspired European monarchs to invest in exploration and conquest. Reports of Spanish atrocities spread throughout Europe and provided a humanitarian justification for European colonization. An English reprint of the writings of Bartolomé de Las Casas bore the sensational title "Popery Truly Display'd in its Bloody Colours: Or, a Faithful Narrative of the Horrid and Unexampled Massacres, Butcheries, and all manners of Cruelties that Hell and Malice could invent, committed past the Popish Spanish." An English writer explained that Native Americans "were simple and plain men, and lived without groovy labour," but in their lust for gold the Spaniards "forced the people (that were not used to labour) to stand up all the daie in the hot sun gathering gilt in the sand of the rivers. By this means a bully number of them (non used to such pains) died, and a great number of them (seeing themselves brought from then serenity a life to such misery and slavery) of desperation killed themselves. And many would not ally, because they would not have their children slaves to the Spaniards."5 The Spanish accused their critics of fostering a "Black Legend." The Black Legend drew on religious differences and political rivalries. Spain had successful conquests in French republic, Italy, Germany, and kingdom of the netherlands and left many in those nations yearning to intermission gratis from Spanish influence. English writers argued that Spanish barbarities were foiling a tremendous opportunity for the expansion of Christianity across the world and that a benevolent conquest of the New World past non-Spanish monarchies offered the surest salvation of the New World'south pagan masses. With these religious justifications, and with obvious economic motives, Espana'south rivals arrived in the New World.

The French

The French crown subsidized exploration in the early sixteenth century. Early French explorers sought a fabled Northwest Passage, a mythical waterway passing through the North American continent to Asia. Despite the wealth of the New World, Asia's riches all the same beckoned to Europeans. Canada'southward St. Lawrence River appeared to be such a passage, stretching deep into the continent and into the Great Lakes. French colonial possessions centered on these bodies of water (and, afterward, down the Mississippi River to the port of New Orleans).

French colonization developed through investment from private trading companies. Traders established Port Imperial in Acadia (Nova Scotia) in 1603 and launched trading expeditions that stretched down the Atlantic coast as far equally Cape Cod. The needs of the fur trade set the time to come pattern of French colonization. Founded in 1608 under the leadership of Samuel de Champlain, Quebec provided the foothold for what would become New France. French fur traders placed a college value on cooperating with Ethnic people than on establishing a successful French colonial footprint. Asserting dominance in the region could take been to their ain detriment, as it might have compromised their access to skilled Native American trappers, and therefore wealth. Few Frenchmen traveled to the New World to settle permanently. In fact, few traveled at all. Many persecuted French Protestants (Huguenots) sought to emigrate afterward France criminalized Protestantism in 1685, only all not-Catholics were forbidden in New French republic.6

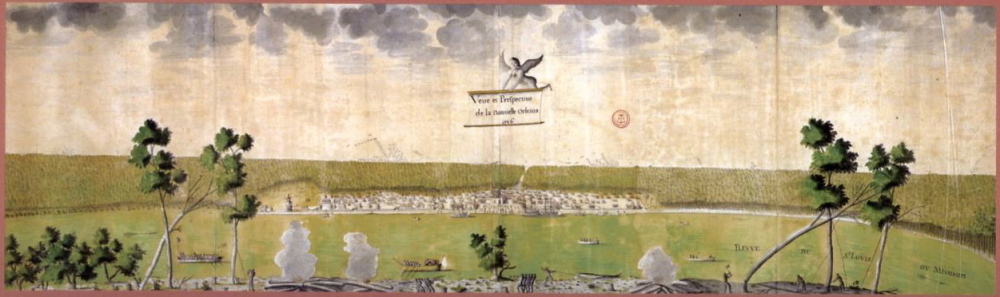

This depiction of New Orleans in 1726 when it was an eight-year-old French frontier settlement. Jean-Pierre Lassus, Veüe et Perspective de la Nouvelle Orleans, 1726, Heart des archives d'outre-mer, France. Wikimedia.

The French preference for trade over permanent settlement fostered more cooperative and mutually beneficial relationships with Native Americans than was typical amid the Castilian and English. Peradventure eager to debunk the anti-Catholic elements of the Black Legend, the French worked to cultivate cooperation with Native Americans. Jesuit missionaries, for instance, adopted different conversion strategies than the Spanish Franciscans. Castilian missionaries brought Natives into enclosed missions, whereas Jesuits more often lived with or alongside Indeneous people. Many French fur traders married Native American women.7 The offspring of Native American women and French men were and then common in New France that the French adult a word for these children, Métis(sage). The Huron people developed a particularly close relationship with the French, and many converted to Christianity and engaged in the fur trade. But close relationships with the French would come up at a high price. The Huron were decimated past the ravages of European disease, and entanglements in French and Dutch conflicts proved disastrous.8 Despite this, some Native peoples maintained alliances with the French.

Pressure level from the powerful Iroquois in the East pushed many Algonquian-speaking peoples toward French territory in the midseventeenth century, and together they crafted what historians have called a "middle ground," a kind of cross-cultural space that allowed for native and European interaction, negotiation, and accommodation. French traders adopted—sometimes clumsily—the souvenir-giving and mediation strategies expected of Native leaders. Natives similarly engaged the impersonal European market and adjusted—often haphazardly—to European laws. The Nifty Lakes "middle ground" experienced tumultuous success throughout the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries until English colonial officials and American settlers swarmed the region. The pressures of European expansion strained even the closest bonds.9

The Dutch

The netherlands, a small maritime nation with great wealth, accomplished considerable colonial success. In 1581, the Netherlands had officially broken abroad from the Hapsburgs and won a reputation as the freest of the new European nations. Dutch women maintained carve up legal identities from their husbands and could therefore hold property and inherit full estates.

Ravaged by the turmoil of the Reformation, the Dutch embraced greater religious tolerance and freedom of the press than other European nations.10 Radical Protestants, Catholics, and Jews flocked to the netherlands. The English Pilgrims, for instance, fled kickoff to the Netherlands before sailing to the New World years afterward. The Netherlands congenital its colonial empire through the work of experienced merchants and skilled sailors. The Dutch were the most advanced capitalists in the modernistic globe and marshaled all-encompassing financial resources by creating innovative financial organizations such every bit the Amsterdam Stock Substitution and the Dutch Due east Republic of india Visitor. Although the Dutch offered liberties, they offered very little democracy—ability remained in the easily of only a few. And Dutch liberties certainly had their limits. The Dutch advanced the slave trade and brought enslaved Africans with them to the New Earth. Slavery was an essential part of Dutch capitalist triumphs.

Sharing the European hunger for access to Asia, in 1609 the Dutch deputed the Englishman Henry Hudson to discover the fabled Northwest Passage through North America. He failed, of course, but nevertheless constitute the Hudson River and claimed mod-day New York for the Dutch. At that place they established New Netherland, an essential part of the Dutch New Earth empire. Holland chartered the Dutch West India Visitor in 1621 and established colonies in Africa, the Caribbean area, and N America. The island of Manhattan provided a launching pad to support its Caribbean colonies and attack Spanish trade.

Spiteful of the Spanish and mindful of the Blackness Fable, the Dutch were adamant non to repeat Castilian atrocities. They fashioned guidelines for New Netherland that conformed to the ideas of Hugo Grotius, a legal philosopher who believed that Native peoples possessed the same natural rights as Europeans. Colony leaders insisted that state exist purchased; in 1626 Peter Minuit therefore "bought" Manhattan from Munsee people.eleven Despite the seemingly honorable intentions, it is likely the Dutch paid the wrong people for the land (either intentionally or unintentionally) or that the Munsee and the Dutch understood the transaction in very different terms. Transactions like these illustrated both the Dutch endeavour to find a more peaceful process of colonization and the inconsistency between European and Native American understandings of property.

Similar the French, the Dutch sought to turn a profit, not to conquer. Trade with Native peoples became New Netherland's central economical activity. Dutch traders carried wampum forth Native trade routes and exchanged information technology for beaver pelts. Wampum consisted of beat chaplet fashioned by Algonquians on the southern New England coast and was valued as a formalism and diplomatic article among the Iroquois. Wampum became a currency that could buy anything from a loaf of bread to a plot of land.12

In addition to developing these trading networks, the Dutch also established farms, settlements, and lumber camps. The Due west Bharat Company directors implemented the patroon organisation to encourage colonization. The patroon system granted large estates to wealthy landlords, who later on paid passage for the tenants to work their land. Expanding Dutch settlements correlated with deteriorating relations with local Native Americans. In the interior of the continent, the Dutch retained valuable alliances with the Iroquois to maintain Beverwijck, modern-twenty-four hours Albany, as a hub for the fur merchandise.thirteen In the places where the Dutch built permanent settlements, the ideals of peaceful colonization succumbed to the settlers' increasing demand for land. Armed conflicts erupted as colonial settlements encroached on Native villages and hunting lands. Profit and peace, it seemed, could not coexist.

Labor shortages, meanwhile, crippled Dutch colonization. The patroon arrangement failed to bring enough tenants, and the colony could not attract a sufficient number of indentured servants to satisfy the colony's backers. In response, the colony imported eleven enslaved people owned by the visitor in 1626, the same yr that Minuit purchased Manhattan. Enslaved laborers were tasked with building New Amsterdam (modern-24-hour interval New York City), including a defensive wall along the northern edge of the colony (the site of mod-day Wall Street). They created its roads and maintained its all-important port. Fears of racial mixing led the Dutch to import enslaved women, enabling the formation of African Dutch families. The colony'south kickoff African marriage occurred in 1641, and by 1650 there were at least five hundred enslaved Africans in the colony. By 1660, New Amsterdam had the largest urban enslaved population on the continent.14

Equally was typical of the practice of African slavery in much of the early seventeenth century, Dutch slavery in New Amsterdam was less comprehensively exploitative than afterwards systems of American slavery. Some enslaved Africans, for instance, successfully sued for back wages. When several enslaved people owned by the company fought for the colony confronting the Munsee, they petitioned for their liberty and won a kind of "half liberty" that allowed them to piece of work their own land in render for paying a large tithe, or tax, to their enslavers. The children of these "half-gratuitous" laborers remained held in chains past the West India Company, however. The Dutch, who and so proudly touted their liberties, grappled with the reality of African slavery, and some New Netherlanders protested the enslavement of Christianized Africans. The economic goals of the colony slowly crowded out these cultural and religious objections, and the much-boasted liberties of the Dutch came to exist alongside increasingly vicious systems of slavery.

The Portuguese

The Portuguese had been leaders in Atlantic navigation well ahead of Columbus's voyage. But the incredible wealth flowing from New Spain piqued the rivalry between the ii Iberian countries, and accelerated Portuguese colonization efforts. This rivalry created a crunch within the Cosmic world as Spain and Portugal squared off in a battle for colonial supremacy. The pope intervened and divided the New World with the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494. Land east of the Tordesillas Peak, an imaginary line dividing South America, would be given to Portugal, whereas land w of the line was reserved for Spanish conquest. In return for the license to conquer, both Portugal and Spain were instructed to care for the natives with Christian compassion and to bring them under the protection of the Church building.

Lucrative colonies in Africa and India initially preoccupied Portugal, just by 1530 the Portuguese turned their attention to the land that would become Brazil, driving out French traders and establishing permanent settlements. Golden and silver mines dotted the interior of the colony, but two industries powered early colonial Brazil: sugar and the slave trade. In fact, over the entire history of the Atlantic slave trade, more Africans were enslaved in Brazil than in whatever other colony in the Atlantic World. Golden mines emerged in greater numbers throughout the eighteenth century just still never rivaled the profitability of sugar or slave trading.

Jesuit missionaries brought Christianity to Brazil, merely potent elements of African and Native spirituality mixed with orthodox Catholicism to create a unique religious culture. This culture resulted from the demographics of Brazilian slavery. High mortality rates on sugar plantations required a steady influx of new enslaved laborers, thus perpetuating the cultural connection betwixt Brazil and Africa. The reliance on new imports of enslaved laborers increased the likelihood of resistance, nonetheless, and those who escaped slavery managed to create several free settlements, called quilombos. These settlements drew from both enslaved Africans and Natives, and despite frequent attacks, several endured throughout the long history of Brazilian slavery.15

Despite the arrival of these new Europeans, Spain connected to dominate the New Earth. The wealth flowing from the exploitation of the Aztec and Incan Empires greatly eclipsed the profits of other European nations. But this dominance would not final long. By the cease of the sixteenth century, the powerful Castilian Armada would be destroyed, and the English would brainstorm to rule the waves.

IV. English Colonization

Nicholas Hilliard, The Battle of Gravelines, 1588. Wikimedia

Spain had a i-hundred-year head commencement on New World colonization, and a jealous England eyed the enormous wealth that Spain gleaned. The Protestant Reformation had shaken England, but Elizabeth I assumed the English crown in 1558. Elizabeth oversaw England'southward so-called gold age, which included both the expansion of merchandise and exploration and the literary achievements of Shakespeare and Marlowe. English mercantilism, a state-assisted manufacturing and trading system, created and maintained markets. The markets provided a steady supply of consumers and laborers, stimulated economical expansion, and increased English language wealth.

All the same, wrenching social and economic changes unsettled the English language population. The island's population increased from fewer than iii million in 1500 to over five million by the middle of the seventeenth century.16 The skyrocketing cost of land coincided with plummeting farming income. Rents and prices rose but wages stagnated. Moreover, movements to enclose public country—sparked past the transition of English landholders from agriculture to livestock raising—evicted tenants from the land and created hordes of landless, jobless peasants that haunted the cities and countryside. 1 quarter to one half of the population lived in farthermost poverty.17

New World colonization won back up in England amid a time of rising English fortunes among the wealthy, a tense Castilian rivalry, and mounting internal social unrest. Merely supporters of English colonization always touted more than economic gains and mere national self-interest. They claimed to be doing God's work. Many claimed that colonization would glorify God, England, and Protestantism past Christianizing the New World's pagan peoples. Advocates such as Richard Hakluyt the Younger and John Dee, for example, drew upon The History of the Kings of United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, written by the twelfth-century monk Geoffrey of Monmouth, and its mythical account of Rex Arthur's conquest and Christianization of pagan lands to justify American conquest.xviii Moreover, promoters promised that the conversion of New Globe Native Americans would satisfy God and glorify England's "Virgin Queen," Elizabeth I, who was seen as well-nigh divine by some in England. The English language—and other European Protestant colonizers—imagined themselves superior to the Castilian, who nonetheless bore the Black Legend of inhuman cruelty. English colonization, supporters argued, would show that superiority.

In his 1584 "Discourse on Western Planting," Richard Hakluyt amassed the supposed religious, moral, and exceptional economical benefits of colonization. He repeated the Blackness Legend of Spanish New World terrorism and attacked the sins of Cosmic Spain. He promised that English language colonization could strike a accident against Spanish heresy and bring Protestant religion to the New World. English language interference, Hakluyt suggested, might provide the only salvation from Cosmic rule in the New World. The New World, besides, he said, offered obvious economic advantages. Trade and resource extraction would enrich the English treasury. England, for instance, could find plentiful materials to outfit a world-class navy. Moreover, he said, the New World could provide an escape for England's vast armies of landless "vagabonds." Expanded trade, he argued, would not merely bring profit but too provide work for England's jobless poor. A Christian enterprise, a blow against Kingdom of spain, an economical stimulus, and a social safety valve all beckoned the English language toward a delivery to colonization.19

This noble rhetoric veiled the coarse economic motives that brought England to the New Globe. New economic structures and a new merchant class paved the way for colonization. England'southward merchants lacked estates, but they had new plans to build wealth. By collaborating with new government-sponsored trading monopolies and employing financial innovations such as joint-stock companies, England's merchants sought to improve on the Dutch economy. Kingdom of spain was extracting enormous cloth wealth from the New Globe; why shouldn't England? Joint-stock companies, the ancestors of modern corporations, became the initial instruments of colonization. With government monopolies, shared profits, and managed risks, these money-making ventures could attract and manage the vast capital needed for colonization. In 1606 James I approved the formation of the Virginia Visitor (named afterward Elizabeth, the Virgin Queen).

Rather than formal colonization, however, the most successful early English language ventures in the New World were a form of state-sponsored piracy known as privateering. Queen Elizabeth sponsored sailors, or "Sea Dogges," such as John Hawkins and Francis Drake, to plunder Spanish ships and towns in the Americas. Privateers earned a substantial profit both for themselves and for the English crown. England skilful piracy on a scale, 1 historian wrote, "that transforms criminal offense into politics."20 Francis Drake harried Spanish ships throughout the Western Hemisphere and raided Spanish caravans as far abroad as the declension of Peru on the Pacific Ocean. In 1580 Elizabeth rewarded her skilled pirate with knighthood. Merely Elizabeth walked a fine line. With Protestant-Cosmic tensions already running high, English privateering provoked Spain. Tensions worsened after the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, a Catholic. In 1588, King Philip 2 of Spain unleashed the fabled Armada. With 130 ships, 8,000 sailors, and 18,000 soldiers, Spain launched the largest invasion in history to destroy the British navy and depose Elizabeth.

An isle nation, England depended on a robust navy for trade and territorial expansion. England had fewer ships than Spain, simply they were smaller and swifter. They successfully harassed the armada, forcing it to retreat to the Netherlands for reinforcements. Just then a fluke tempest, celebrated in England as the "divine wind," annihilated the residue of the fleet.21 The destruction of the armada inverse the grade of world history. It not only saved England and secured English Protestantism, simply it too opened the seas to English language expansion and paved the manner for England'south colonial hereafter. By 1600, England stood ready to embark on its dominance over North America.

English colonization would wait very different from Spanish or French colonization. England had long been trying to conquer Catholic Ireland. Rather than integrating with the Irish and trying to convert them to Protestantism, England more frequently merely seized country through violence and pushed out the former inhabitants, leaving them to move elsewhere or to die. These same tactics would later be deployed in North American invasions.

English language colonization, however, began haltingly. Sir Humphrey Gilbert labored throughout the tardily sixteenth century to establish a colony in Newfoundland only failed. In 1587, with a predominantly male person cohort of 150 English colonizers, John White reestablished an abased settlement on North Carolina'due south Roanoke Island. Supply shortages prompted White to render to England for additional back up, but the Spanish Fleet and the mobilization of British naval efforts stranded him in U.k. for several years. When he finally returned to Roanoke, he found the colony abased. What befell the failed colony? White plant the word Croatoan carved into a tree or a mail service in the abandoned colony. Historians presume the colonists, short of nutrient, may have fled for a nearby island of that name and encountered its settled native population. Others offer violence as an explanation. Regardless, the English colonists were never heard from once more. When Queen Elizabeth died in 1603, no Englishmen had yet established a permanent North American colony.

After King James fabricated peace with Spain in 1604, privateering no longer held out the promise of cheap wealth. Colonization causeless a new urgency. The Virginia Visitor, established in 1606, drew inspiration from Cortés and the Spanish conquests. It hoped to find gold and silvery too equally other valuable trading bolt in the New World: glass, iron, furs, pitch, tar, and annihilation else the state could supply. The visitor planned to place a navigable river with a deep harbor, away from the eyes of the Spanish. There they would find a Native American trading network and excerpt a fortune from the New World.

V. Jamestown

Incolarum Virginiae piscandi ratio (The Method of Fishing of the Inhabitants of Virginia), c. 1590. The Encyclopedia Virginia.

In April 1607 Englishmen aboard 3 ships—the Susan Constant, the Godspeed, and the Discovery—sailed 40 miles upwards the James River (named for the English king) in present-day Virginia (named for Elizabeth I, the Virgin Queen) and settled on just such a place. The uninhabited peninsula they selected was upriver and out of sight of Spanish patrols. Information technology offered easy defense against basis assaults and was both uninhabited and located shut to many Native American villages and their potentially lucrative trade networks. But the location was a disaster. Ethnic people had ignored the peninsula for two reasons: terrible soil hampered agronomics, and brackish tidal water led to debilitating disease. Despite these setbacks, the English congenital Jamestown, the starting time permanent English colony in the present-mean solar day Usa.

The English had not entered a wilderness just had arrived among a people they called the Powhatan Confederacy. Powhatan, or Wahunsenacawh, as he called himself, led about ten chiliad Algonquian-speaking people in the Chesapeake. They burned vast acreage to articulate brush and create sprawling artificial parklike grasslands so they could hands hunt deer, elk, and bison. The Powhatan raised corn, beans, squash, and possibly sunflowers, rotating acreage throughout the Chesapeake. Without plows, manure, or draft animals, the Powhatan produced a remarkable number of calories cheaply and efficiently.

Jamestown was a profit-seeking venture backed by investors. The colonists were mostly gentlemen and proved entirely unprepared for the challenges ahead. They hoped for easy riches but establish none. As John Smith after complained, they "would rather starve than work."22 And and so they did. Disease and starvation ravaged the colonists, thanks in part to the peninsula's unhealthy location and the fact that supplies from England arrived sporadically or spoiled. Fewer than half of the original colonists survived the first 9 months.

John Smith, a yeoman'southward son and capable leader, took command of the crippled colony and promised, "He that will not work shall non eat." He navigated Native American diplomacy, claiming that he was captured and sentenced to expiry just Powhatan's girl, Pocahontas, intervened to salvage his life. She would later on ally some other colonist, John Rolfe, and dice in England.

Powhatan kept the English live that get-go wintertime. The Powhatan had welcomed the English and placed a loftier value on metallic ax-heads, kettles, tools, and guns and eagerly traded furs and other abundant goods for them. With ten yard confederated natives and with food in abundance, Ethnic people had little to fear and much to gain from the isolated outpost of sick and dying Englishmen.

John White, "Hamlet of the Secotan, 1585. Wikimedia.

Despite reinforcements, the English language continued to die. Four hundred settlers arrived in 1609, just the overwhelmed colony entered a desperate "starving time" in the wintertime of 1609–1610. Supplies were lost at bounding main. Relations with Native Americans deteriorated and the colonists fought a kind of slow-burning guerrilla war with the Powhatan. Disaster loomed for the colony. The settlers ate everything they could, roaming the woods for nuts and berries. They boiled leather. They dug up graves to eat the corpses of their one-time neighbors. One man was executed for killing and eating his wife. Some years later, George Percy recalled the colonists' desperation during these years, when he served as the colony's president: "Having fed upon our horses and other beasts as long as they lasted, we were glad to make shift with vermin as dogs, cats, rats and mice . . . every bit to eat boots shoes or whatsoever other leather. . . . And now famine beginning to look ghastly and pale in every face, that nothing was spared to maintain life and to doe those things which seam incredible, as to dig upwards dead corpses out of graves and to swallow them."23 Archaeological excavations in 2012 exhumed the bones of a fourteen-year-old girl that exhibited signs of cannibalism.24 All but sixty settlers would die by the summer of 1610.

Little improved over the next several years. By 1616, eighty per centum of all English language immigrants who had arrived in Jamestown had perished. England'southward first American colony was a catastrophe. The colony was reorganized, and in 1614 the union of Pocahontas to John Rolfe eased relations with the Powhatan, though the colony even so limped along as a starving, commercially disastrous tragedy. The colonists were unable to find whatsoever profitable commodities and remained dependent on Native Americans and sporadic shipments from England for food. But then tobacco saved Jamestown.

By the time King James I described tobacco as a "noxious weed, . . . loathsome to the center, mean to the nose, harmful to the encephalon, and dangerous to the lungs," it had already taken Europe past storm. In 1616 John Rolfe crossed tobacco strains from Trinidad and Guiana and planted Virginia's beginning tobacco crop. In 1617 the colony sent its kickoff cargo of tobacco back to England. The "baneful weed," a native of the New World, fetched a loftier price in Europe and the tobacco boom began in Virginia and and then after spread to Maryland. Within xv years American colonists were exporting over five hundred thou pounds of tobacco per year. Inside forty years, they were exporting xv million.25

Tobacco changed everything. Information technology saved Virginia from ruin, incentivized farther colonization, and laid the groundwork for what would get the United States. With a new market open up, Virginia drew non only merchants and traders only likewise settlers. Colonists came in droves. They were by and large immature, by and large male, and mostly indentured servants who signed contracts called indentures that bonded them to employers for a period of years in render for passage beyond the ocean. But fifty-fifty the rough terms of servitude were no match for the promise of land and potential profits that beckoned English farmers. But still there were not enough of them. Tobacco was a labor-intensive crop and ambitious planters, with seemingly limitless land before them, lacked only laborers to escalate their wealth and status. The colony's dandy labor vacuum inspired the creation of the "headright policy" in 1618: any person who migrated to Virginia would automatically receive fifty acres of land and whatsoever immigrant whose passage they paid would entitle them to fifty acres more.

In 1619, the Virginia Company established the House of Burgesses, a limited representative torso composed of white landowners that first met in Jamestown. That aforementioned year, a Dutch slave send sold twenty Africans to the Virginia colonists. Southern slavery was built-in.

Soon the tobacco-growing colonists expanded beyond the bounds of Jamestown'southward mortiferous peninsula. When it became clear that the English were not just intent on maintaining a small trading mail service but sought a permanent ever-expanding colony, conflict with the Powhatan Confederacy became about inevitable. Powhatan died in 1622 and was succeeded by his brother, Opechancanough, who promised to drive the country-hungry colonists back into the sea. He launched a surprise attack and in a single day (March 22, 1622) killed over 350 colonists, or 1 third of all the colonists in Virginia.26 The colonists retaliated and revisited the massacres on Indigenous settlements many times over. The massacre freed the colonists to bulldoze Native Americans off their state. The governor of Virginia declared it colonial policy to achieve the "expulsion of the savages to gain the gratis range of the country."27 War and disease tilted the balance of ability decisively toward the English language colonizers.

English language colonists brought to the New World detail visions of racial, cultural, and religious supremacy. Despite starving in the shadow of the Powhatan Confederacy, English language colonists still judged themselves physically, spiritually, and technologically superior to Native peoples in N America. Christianity, metallurgy, intensive agriculture, transatlantic navigation, and even wheat all magnified the English sense of superiority. This sense of superiority, when coupled with outbreaks of violence, left the English feeling entitled to Ethnic lands and resources.

Spanish conquerors established the framework for the Atlantic slave merchandise over a century before the offset chained Africans arrived at Jamestown. Even Bartolomé de Las Casas, historic for his pleas to salve Native Americans from colonial butchery, for a time recommended that Indigenous labor exist replaced by importing Africans. Early English settlers from the Caribbean and Atlantic declension of North America generally imitated European ideas of African inferiority. "Race" followed the expansion of slavery beyond the Atlantic world. Pare color and race suddenly seemed fixed. Englishmen equated Africans with categorical blackness and blackness with sin, "the handmaid and symbol of baseness."28 An English language essayist in 1695 wrote that "a negro will always exist a negro, carry him to Greenland, feed him chalk, feed and manage him never and so many ways."29 More and more than Europeans embraced the notions that Europeans and Africans were of distinct races. Others now preached that the Erstwhile Testament God cursed Ham, the son of Noah, and doomed Black people to perpetual enslavement.

And yet in the early years of American slavery, ideas about race were not even so fixed and the practice of slavery was not yet codified. The first generations of Africans in English North America faced miserable atmospheric condition, but, in contrast to afterwards American history, their initial servitude was not necessarily permanent, heritable, or even particularly disgraceful. Africans were definitively prepare apart equally fundamentally different from their white counterparts and faced longer terms of service and harsher punishments, but, similar the indentured white servants whisked away from English language slums, these first Africans in North America could too work for only a prepare number of years earlier becoming free landowners themselves. The Angolan Anthony Johnson, for case, was sold into servitude but fulfilled his indenture and became a prosperous tobacco planter himself.30

In 1622, at the dawn of the tobacco nail, Jamestown had still seemed a failure. But the rise of tobacco and the destruction of the Powhatan turned the tide. Colonists escaped the deadly peninsula and immigrants poured into the colony to grow tobacco and plow a profit for the Crown.

VI. New England

The English language colonies in New England established from 1620 onward were founded with loftier goals than those in Virginia. Although migrants to New England expected economic profit, religious motives directed the rhetoric and much of the reality of these colonies. Not every English person who moved to New England during the seventeenth century was a Puritan, but Puritans dominated the politics, religion, and culture of New England. Even after 1700, the region's Puritan inheritance shaped many aspects of its history.

The term Puritan began equally an insult, and its recipients normally referred to each other every bit "the godly" if they used a specific term at all. Puritans believed that the Church of England did not altitude itself far enough from Catholicism later on Henry Eight broke with Rome in the 1530s. They largely agreed with European Calvinists—followers of theologian John Calvin—on matters of religious doctrine. Calvinists (and Puritans) believed that humankind was redeemed by God'south grace lonely, and that the fate of an private's immortal soul was predestined. The happy minority that God had already called to salvage were known amongst English Puritans as the Elect. Calvinists besides argued that the decoration of churches, reliance on ornate ceremony, and corrupt priesthood obscured God's message. They believed that reading the Bible was the best fashion to sympathize God.

Puritans were stereotyped past their enemies as dour killjoys, and the exaggeration has endured. It is certainly truthful that the Puritans' disdain for excess and opposition to many holidays popular in Europe (including Christmas, which, as Puritans never tired of reminding everyone, the Bible never told anyone to celebrate) lent themselves to extravaganza. Only Puritans understood themselves as advocating a reasonable middle path in a corrupt earth. Information technology would never occur to a Puritan, for case, to abjure from alcohol or sex.

During the first century after the English language Reformation (c. 1530–1630) Puritans sought to "purify" the Church of England of all practices that smacked of Catholicism, advocating a simpler worship service, the abolitionism of ornate churches, and other reforms. They had some success in pushing the Church of England in a more Calvinist direction, but with the coronation of King Charles I (r. 1625–1649), the Puritans gained an implacable foe that cast English Puritans every bit excessive and dangerous. Facing growing persecution, the Puritans began the Great Migration, during which about xx thousand people traveled to New England betwixt 1630 and 1640. The Puritans (dissimilar the small band of separatist "Pilgrims" who founded Plymouth Colony in 1620) remained committed to reforming the Church of England but temporarily decamped to North America to accomplish this task. Leaders like John Winthrop insisted they were not separating from, or abandoning, England but were rather forming a godly community in America that would be a "City on a Colina" and an instance for reformers dorsum dwelling house.31 The Puritans did not seek to create a oasis of religious toleration, a notion that they—along with most all European Christians—regarded as ridiculous at best and dangerous at worst.

While the Puritans did not succeed in building a godly utopia in New England, a combination of Puritan traits with several external factors created colonies wildly different from any other region settled by English people. Unlike those heading to Virginia, colonists in New England (Plymouth [1620], Massachusetts Bay [1630], Connecticut [1636], and Rhode Island [1636]) generally arrived in family groups. Well-nigh New England immigrants were small landholders in England, a class gimmicky English chosen the "middling sort." When they arrived in New England they tended to replicate their habitation environments, founding towns equanimous of independent landholders. The New England climate and soil made large-scale plantation agriculture impractical, so the organisation of large landholders using masses of enslaved laborers or indentured servants to grow labor-intensive crops never took concur.

There is no prove that the New England Puritans would have opposed such a arrangement were it possible; other Puritans fabricated their fortunes on the Caribbean saccharide islands, and New England merchants profited equally suppliers of provisions and enslaved laborers to those colonies. By accident of geography as much as by design, New England society was much less stratified than any of United kingdom'southward other seventeenth-century colonies.

Although New England colonies could boast wealthy landholding elites, the disparity of wealth in the region remained narrow compared to the Chesapeake, Carolina, or the Caribbean area. Instead, seventeenth-century New England was characterized by a broadly shared modest prosperity based on a mixed economy dependent on small farms, shops, angling, lumber, shipbuilding, and trade with the Atlantic World.

A combination of environmental factors and the Puritan social ethos produced a region of remarkable health and stability during the seventeenth century. New England immigrants avoided well-nigh of the mortiferous outbreaks of tropical disease that turned the Chesapeake colonies into graveyards. Disease, in fact, only aided English language settlement and relations to Native Americans. In contrast to other English colonists who had to debate with powerful Native American neighbors, the Puritans confronted the stunned survivors of a biological ending. A lethal pandemic of smallpox during the 1610s swept away as much every bit ninety percent of the region's Native American population. Many survivors welcomed the English equally potential allies against rival tribes who had escaped the ending. The relatively healthy environment coupled with political stability and the predominance of family groups amidst early immigrants allowed the New England population to abound to 91,000 people by 1700 from merely 21,000 immigrants. In contrast, 120,000 English went to the Chesapeake, and only 85,000 white colonists remained in 1700.32

The New England Puritans set out to build their utopia by creating communities of the godly. Groups of men, often from the same region of England, practical to the colony'due south Full general Court for country grants.33 They generally divided role of the land for immediate utilise while keeping much of the remainder as "commons" or undivided land for future generations. The boondocks's inhabitants collectively decided the size of each settler's habitation lot based on their current wealth and status. Too oversight of belongings, the boondocks restricted membership, and new arrivals needed to apply for access. Those who gained admittance could participate in town governments that, while not democratic by modern standards, nevertheless had broad pop interest. All male person property holders could vote in town meetings and choose the selectmen, assessors, constables, and other officials from amongst themselves to conduct the daily affairs of government. Upon their founding, towns wrote covenants, reflecting the Puritan belief in God'due south covenant with his people. Towns sought to arbitrate disputes and contain strife, as did the Church. Wayward or divergent individuals were persuaded, corrected, or coerced. Popular conceptions of Puritans as hardened authoritarians are exaggerated, but if persuasion and arbitration failed, people who did not suit to community norms were punished or removed. Massachusetts banished Anne Hutchinson, Roger Williams, and other religious dissenters like the Quakers.

Although by many measures colonization in New England succeeded, its Puritan leaders failed in their own mission to create a utopian community that would inspire their fellows back in England. They tended to focus their disappointment on the younger generation. "But alas!" Increase Mather lamented, "That so many of the younger Generation have and so early on corrupted their [the founders'] doings!"34 The jeremiad, a sermon lamenting the fallen country of New England due to its straying from its early virtuous path, became a staple of late-seventeenth-century Puritan literature.

Yet the jeremiad could not stop the effects of prosperity. The population spread and grew more diverse. Many, if not most, New Englanders retained strong ties to their Calvinist roots into the eighteenth century, but the Puritans (who became Congregationalists) struggled against a rising tide of religious pluralism. On December 25, 1727, Judge Samuel Sewell noted in his diary that a new Anglican minister "keeps the day in his new Church at Braintrey: people flock thither."35 Previously forbidden holidays like Christmas were historic publicly in church building and privately in homes. Puritan divine Cotton Mather discovered on Christmas 1711 that "a number of immature people of both sexes, belonging, many of them, to my flock, had . . . a Frolick, a reveling Feast, and a Ball, which discovers their Corruption."36

Despite the lamentations of the Mathers and other Puritan leaders of their failure, they left an indelible mark on New England culture and society that endured long later on the region's residents ceased to be called "Puritan."

VII. Conclusion

The fledgling settlements in Virginia and Massachusetts paled in importance when compared to the carbohydrate colonies of the Caribbean. Valued more as marginal investments and social rubber valves where the poor could be released, these colonies nonetheless created a foothold for Uk on a vast North American continent. And although the seventeenth century would be fraught for Britain—religious, social, and political upheavals would decollate 1 rex and force some other to flee his throne—settlers in Massachusetts and Virginia were nonetheless tied together past the emerging Atlantic economy. While commodities such as tobacco and carbohydrate fueled new markets in Europe, the economy grew increasingly dependent on slave labor. Enslaved Africans transported beyond the Atlantic would further complicate the collision of cultures in the Americas. The cosmos and maintenance of a slave arrangement would spark new understandings of human divergence and new modes of social command. The economic exchanges of the new Atlantic economy would not only generate dandy wealth and exploitation, they would too atomic number 82 to new cultural systems and new identities for the inhabitants of at least 4 continents.

Viii. Primary Sources

1. Richard Hakluyt makes the case for English colonization, 1584

Richard Hakluyt used this document to persuade Queen Elizabeth I to devote more coin and free energy into encouraging English colonization. In xx-one chapters, summarized here, Hakluyt emphasized the many benefits that England would receive by creating colonies in the Americas.

two. John Winthrop dreams of a metropolis on a loma, 1630

John Winthrop delivered the following sermon earlier he and his fellow settlers reached New England . The sermon is famous largely for its apply of the phrase "a city on a hill," used to describe the expectation that the Massachusetts Bay colony would shine like an case to the world. Just Winthrop'south sermon also reveals how he expected Massachusetts to differ from the rest of the world.

3. John Lawson encounters Native Americans, 1709

John Lawson took detailed notes on the various peoples he encountered during his exploration of the Carolinas. Lawson recorded many aspects of Native American life and even noticed the progress of disease equally it swept through native communities.

4. A Gaspesian human being defends his mode of life, 1641

Chrestien Le Clercq traveled to New France equally a missionary, simply found that many Native Americans were not interested in adopting European cultural practices. In this document, LeClercq records the words of a Gaspesian man who explained why he believed that his way of life was superior to Le Clercq's.

v. The fable of Moshup, 1830

Most Native American peoples shared information solely through the spoken word. These oral cultures present unique challenges to historians, and force us to await beyond traditional written sources. Folk tales offer a valuable window into the ways that Native Americans understood themselves and the wider world. The Wampanoag fable of Moshup describes an aboriginal giant who lived on Martha's Vineyard Island and offered stories well-nigh the history of the region.

6. Accusations of witchcraft, 1692 and 1706

These two documents explore the hysteria and death that captured Salem, Massachusetts at the finish of the seventeenth century. In the first document, Sarah Carrier testifies that her female parent forced her to engage in witchcraft. Her mother, Martha Carrier, was hung one week afterwards. In the 2nd document, Ann Putnam recants her ain deadly accusations xx years after the witchcraft trials.

vii. Manuel Trujillo accuses Asencio Povia and Antonio Yuba of sodomy, 1731

In 1731, Manuel Trujillo accused two Pueblo men, Acensio Povia and Antonio Yuba, of committing sodomy. Both Povia and Yuba denied this accusation, and Yuba invoked his condition equally a Christian in order to bolster his credibility. Governor Gervasio Cruzat y Góngora chose to exile Povia and Yuba to different pueblos for a period of iv months, during which time they were to cease any and all communication with 1 another. This case explores sexual practices deemed "nefarious sins" as well as illustrates what scholars have called the colonial dilemma—the state of affairs where Ethnic peoples remained in a subjected land despite theological equality following their Christian conversion.

8. Painting of New Orleans, 1726

During the contact period, the frontier was constantly shifting and places that are now considered erstwhile were once tenuous settlements. This watercolor painting depicts New Orleans in 1726 when it was an 8-yr-sometime French borderland settlement, nigh forty years prior to the Spanish acquisition of the Louisiana territory. In the foreground, enslaved Africans savage copse on land belonging to the Company of the Indies, and another enslaved human spears a massive alligator. Land has been cleared but just beyond the town limits and a wooden palisade provides meager protection from competing European empires.

ix. Sketch of Algonquin village, 1585

Native settlements were usually organized around political, economic, or religious activity. John White shows this Algonquin community engaged in some kind of celebration across from the fire he identified equally "The place of solemne prayer," indicating that ceremonial action could be both solemn and raucous. In the center of the image, a communal meal has been laid alongside crops that are in varying stages of growth, suggesting the use of planting techniques like crop rotation. He also shows the interior of several longhouses, fabricated of bent saplings and covered with bark and woven maps. Amidst the Powhatan, similar structures were called yehakins. In putting the longhouses and the settlement in a serial of rows, White's English perspective comes through: archaeological evidence shows that these houses were ordinarily situated around communal gathering places or moved next to fields nether cultivation non ordered in European-manner rows.

Ix. Reference Materials

This chapter was edited by Ben Wright and Joseph Locke, with content contributions by Erin Bonuso, Fifty. D. Burnett, Jon Grandage, Joseph Locke, Lisa Mercer, Maria Montalvo, Ian Saxine, Jennifer Tellman, Luke Willert, and Ben Wright.

Recommended citation: Erin Bonuso et al., "Colliding Cultures," Ben Wright and Joseph L. Locke, eds., in The American Yawp, eds. Joseph L. Locke and Ben Wright (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018).

Recommended Reading

- Armitage, David, and Michael J. Braddick, eds. The British Atlantic World, 1500–1800. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002.

- Barr, Juliana. Peace Came in the Form of a Woman: Indians and Spaniards in the Texas Borderlands. Chapel Hill: University of N Carolina Press, 2009.

- Blackburn, Robin. The Making of New World Slavery: From the Baroque to the Modern, 1492–1800. London: Verso, 1997.

- Calloway, Colin One thousand. New Worlds for All: Indians, Europeans, and the Remaking of Early America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

- Cañizares-Esguerra, Jorge. Puritan Conquistadors. Iberianizing the Atlantic, 1550–1700. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2006.

- Cronon, William. Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England. New York: Loma and Wang, 1983.

- Daniels, Christine, and Michael V. Kennedy, eds. Negotiated Empires: Centers and Peripheries in the Americas, 1500–1820. New York: Routledge, 2002.

- Dubcovsky, Alejandra. Informed Power: Advice in the Early American South. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016.

- Elliott, John H. Empires of the Atlantic Globe: United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland and Espana in America, 1492–1830. New Haven, CT: Yale Academy Press, 2006.

- Fuentes, Marisa J. Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

- Goetz, Rebecca Anne. The Baptism of Early on Virginia: How Christianity Created Race. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012.

- Gould, Eliga H. "Entangled Histories, Entangled Worlds: The English language-Speaking Atlantic every bit a Spanish Periphery." American Historical Review 112, no. 3 (June 2007): 764-786.

- Grandjean, Katherine. American Passage: The Communications Frontier in Early New England. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015.

- Mancall, Peter C. Hakluyt's Promise: An Elizabethan'due south Obsession for an English language America. New Oasis, CT: Yale University Printing, 2007.

- Morgan, Edmund South. American Slavery, American Liberty: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia. New York: Norton, 1975.

- Morgan, Jennifer. Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004.

- Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017.

- Seed, Patricia. Ceremonies of Possession in Europe's Conquest of the New Globe, 1492–1640. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Snyder, Christina. Slavery in Indian State: The Changing Face of Captivity in Early America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010.

- Socolow, Susan Migden. The Women of Colonial Latin America. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Stoler, Ann Laura. "Tense and Tender Ties: The Politics of Comparison in N American History and (Post) Colonial Studies." Journal of American History 88, no. iii (December 2001): 829–897.

- Thornton, John. Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800. New York: Cambridge University Printing, 1992.

- Warren, Wendy. New England Leap: Slavery and Colonization in Early America. New York: Norton, 2016.

- Weimer, Adrian. Martyrs' Mirror: Persecution and Holiness in Early New England. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- White, Richard. The Center Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650–1815. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Notes

- Stanley Fifty. Engerman and Robert E. Gallman, eds., The Cambridge Economical History of the United States, Vol. I: The Colonial Era (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 21. [↩]

- Andrew L. Knaut,The Pueblo Revolt of 1680: Conquest and Resistance in Seventeenth Century New Mexico (Norman: Academy of Oklahoma Press, 2015), 46. [↩]

- John E. Kicza and Rebecca Horn, Resilient Cultures: America's Native Peoples Face European Colonization, 1500–1800 (New York: Routledge, 2013), 122. [↩]

- Knaut, Pueblo Revolt of 1680, 155. [↩]

- John Ponet, A Brusque Treatise on Political Ability: And of the Truthful Obedience Which Subjects Owe to Kings, and Other Civil Governors (London: s.n.), 43–44. [↩]

- Alan Greer, The People of New France (Toronto: Academy of Toronto Press, 1997). [↩]

- Susan Sleeper-Smith, Indian Women and French Men: Rethinking Cultural Come across in the Western Great Lakes (Amherst: Academy of Massachusetts Printing, 2001). [↩]

- Carole Blackburn, Harvest of Souls: The Jesuit Missions and Colonialism in Due north America, 1632–1659 (Montreal: McGill-Queen's Academy Press, 2000), 116. [↩]

- Richard White, The Middle Footing: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650–1815 (New York: Cambridge University Printing, 1991). [↩]

- Evan Haefeli, New Netherland and the Dutch Origins of American Religious Liberty (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Printing, 2012), 20–53. [↩]

- Allen W. Trelease, Indian Affairs in Colonial New York: The Seventeenth Century (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997), 36. [↩]

- Daniel Thousand. Richter, Merchandise, Land, Power: The Struggle for Eastern North America (Philadelphia: Academy of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), 101. [↩]

- Janny Venema, Beverwijck: A Dutch Village on the American Frontier, 1652–1664 (Albany: SUNY Press, 2003). [↩]

- Leslie M. Harris, In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626–1863 (Chicago: Academy of Chicago Press, 2003), 21. [↩]

- Alida C. Metcalf, Go-betweens and the Colonization of Brazil: 1500–1600 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005). Meet as well James H. Sweet, Recreating Africa: Culture, Kinship, and Faith in the African-Portuguese World, 1441–1770 (Chapel Loma: Academy of North Carolina Printing, 2003. [↩]

- Edmund S. Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia (New York: Norton, 1975), 30. [↩]

- John Walter, Crowds and Popular Politics in Early on Modernistic England (Manchester, Britain: Manchester Academy Press, 2006), 131–135. [↩]

- Christopher Hodgkins, Reforming Empire: Protestant Colonialism and Conscience in British Literature (Columbia: Academy of Missouri Press, 2002), 15. [↩]

- Richard Hakluyt, Discourse on Western Planting (1584). https://archive.org/details/discourseonweste02hakl_0. [↩]

- Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom, 9. [↩]

- Felipe Fernández-Armesto, The Spanish Fleet: The Feel of War in 1588 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988). [↩]

- John Smith, Advertisements for the Inexperienced Planters of New England, or Anywhere or The Pathway to Experience to Cock a Plantation (London: Haviland, 1631), 16. [↩]

- George Percy, "A Truthful Relation of the Proceedings and Occurrents of Moment Which Have Hap'ned in Virginia," quoted in Jamestown Narratives: Eyewitness Accounts of the Virginia Colony, the Starting time Decade, 1607–1617, ed. Edward Wright Haile (Champlain, VA: Round House, 1998), 505. [↩]

- Eric A. Powell, "Chilling Discovery at Jamestown," Archaeology (June 10, 2013). http://www.archaeology.org/issues/96-1307/trenches/973-jamestown-starving-time-cannibalism. [↩]

- Dennis Montgomery, 1607: Jamestown and the New World (Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2007), 126. [↩]

- Rebecca Goetz, The Baptism of Early Virginia: How Christianity Created Race (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 57. [↩]

- Daniel Thou. Richter, Facing E from Indian Land: A Native History of Early America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Printing, 2009), 75. [↩]

- Winthrop Jordan, White over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550–12 (Chapel Loma: University of North Carolina Press, 1968), seven. [↩]

- Ibid., 16. [↩]

- T. H. Breen and Stephen Innes, "Myne Owne Ground": Race and Freedom on Virginia'southward Eastern Shore, 1640–1676 (New York: Oxford Academy Printing, 2005). [↩]

- John Winthrop, A Modell of Christian Charity (1630), offset published in Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society (Boston, 1838), 3rd series, no. 7: 31–48. http://history.hanover.edu/texts/winthmod.html. [↩]

- Alan Taylor, American Colonies: The Settling of N America (New York: Penguin, 2002), 170. [↩]

- Virginia DeJohn Anderson, New England's Generation: The Great Migration and the Germination of Society and Civilization in the Seventeenth Century (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 90–91. [↩]

- Increase Mather, A Testimony Confronting Several Prophane and Superstitious Customs, Now Practised by Some in New-England (London: s.due north., 1687). [↩]

- Samuel Sewall, Diary of Samuel Sewall: 1674–1729, Vol. 3 (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1882), 389. [↩]

- Diary of Cotton wool Mather, 1709-724(Boston: Massachusetts Historical Guild, 1912), 146. [↩]

Source: https://www.americanyawp.com/text/02-colliding-cultures/

0 Response to "The Color of Family Ties Race Class Gender and Extended Family Involvement Citation"

Post a Comment